Online video services are broken. Consider the case of Eureka, a fantastic science fiction show about a silly town full of super scientists, which is being canceled like most quality SF because it could never find an audience on broadcast TV. If you want to watch Eureka online, you’re in semi-luck, it’s on Hulu (Plus). However, there’s a catch:

Online video services are broken. Consider the case of Eureka, a fantastic science fiction show about a silly town full of super scientists, which is being canceled like most quality SF because it could never find an audience on broadcast TV. If you want to watch Eureka online, you’re in semi-luck, it’s on Hulu (Plus). However, there’s a catch:

For Syfy scripted television, the first four episodes of every season will be made available online the day after they air. Every episode after the initial four will be available 30 days after air.

5 episodes will be available at a time.

This is an entirely arbitrary limitation that means that I won’t be watching Eureka even though it’s online for at least a month – a month in which newer shows might come along and eat into my limited availability for watching new and exciting television – like Game of Thrones. This, in a nutshell, is why online streaming is no saviour of quality television: because the content is still slaved to broadcast economics. And for the purposes of this discussion, anything on basic cable might as well be broadcast TV. Unless we get true a la carte pricing on cable (which will never happen), this will always remain true.

Erik at Forbes wrote a deservedly widely-linked piece lambasting HBO for refusing to make GoT available outside a premium subscription, pointing out that the restriction has only encouraged rampant piracy. Later, Erik called for HBO to at least allow folks to subscribe to HBO Go as a standalone service, only to later realize that this is untenable from HBO’s perspective due to their business model. In a nutshell, piracy isn’t a threat to HBO’s ability to create quality TV programming – online video services, however, are a mortal threat, especially “cord cutting” (as an excellent rebuttal by Trevor Gilbert at Pando Daily also made quite clear). It’s also worth reading HBO co-president Eric Kesseler’s thoughts on the matter.

The problem is that quality TV is expensive. Great shows like Awake, Terra Nova, and Eureka are all lost, while nonsense like Lost gets renewed for a milion years and people actually were fooled into thinking that’s good television. Once in a while you get something great like Battlestar Galactica that survives barely long enough to tell a story in depth and in full, but these are rare events built on the fertile ground of corpses of superior concepts like Farscape and Firefly.

The rush to the web means that most content companies are reactionary – they grudgingly put the shows online, but they do it half-assed (as in Syfy’s case with Eureka) with inane restrictions that hamper building a viral audience. Netflix doesn’t have any current television at all, the only game in town is Hulu or buying videos from Amazon or iTunes, which rapidly makes even the expense of cable television seem like a bargain. The end result is that the video go online (at significant engineering and overhead cost) but they fail to generate any viral interest – and cannibalize broadcast views, which hurts ratings.

Yes, Nielsen supposedly does count DVR views towards ratings now, but it’s doubtful that’s equally weighted as a faithful viewer sitting down at the annointed timeslot. But even using a DVR is like flying the space shuttle compared to ease-of-use of online, given that every device in your family room has an internet connection now: Wii, XBox, Playstation, smart TV, Roku, Apple TV. All of these support Hulu and/or Netflix or both and most support Amazon video. DVRs are dinosaurs in comparison.

But if DVRs are not counted as equal to a traditional view, then surely Hulu etc is even less. It’s trivial to ignore ads on Hulu by opening a new window and checking your email, or laying the iPad aside and goofing off with your phone for 30 sec. Hulu is very helpful in even giving you a countdown for how much commercial remains.

No matter how you argue yourself an an exception to the rule, it’s a no-brainer that online viewing of television means less ads, less engaged consumers, and lower ratings. And that hurts good TV across the board. It’s harder to persuade a studio to take a risk on a new concept because they know that even if it’s good, they can’t sell as many ads as they used to so the cost-benefit calculation is going to be worse than it was a few years ago, and will get worse further still ahead.

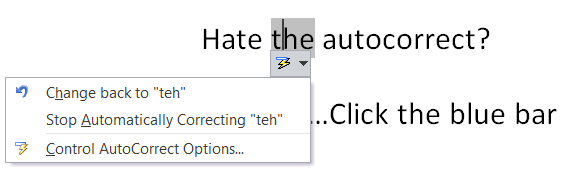

There’s only one alternative for quality television, outside the Clone ARmy of online streaming services, and that is premium television. If SyFy were a premium channel we would be watching Firefly season 5 by now. As long as we circle around the drain of online streaming we are going to see fewer and fewer shows outside that paywall worth watching, and the few that do make it will be short-lived. The cancellation of Awake really burns in this regard – a show that had an incredible idea but just didn’t have the time to mature. Look at the difference between Encounter at Farpoint and Yesterday’s Enterprise or The Offspring, for example. We don’t get to see that kind of maturation anymore because teh economics of ratings has driven it into the ground, and online streaming is the bloody shovel.

The techsphere is all agog over everything mobile, streaming, real-time, immediate gratification, and cheap. But that’s a formula for dren rather than quality. This is why we can’t have nice things.

I’ve just upgraded to the 30 MB/s internet plan at Charter cable (and added HBO so we can watch Game of Thrones), so here’s the obligatory speedtest results.

I’ve just upgraded to the 30 MB/s internet plan at Charter cable (and added HBO so we can watch Game of Thrones), so here’s the obligatory speedtest results.

a wonderfully geeky debate is unfolding about the practicality of Dyson Spheres. Or rather, a subset type called a Dyson Swarm.

a wonderfully geeky debate is unfolding about the practicality of Dyson Spheres. Or rather, a subset type called a Dyson Swarm.  With

With